|

A BIOGRAPHY of John Milton, 1608-1674

BY KATHARINE FLETCHER

I won't lie to you: biographies are often pretty dull, and you might think that the life of a middle-class, well-educated, religious poet born four hundred years ago would be duller than a blunt spoon, but nothing could be further from the truth. Aside from the obvious academic benefit of being able to understand the context of his work, Milton's life is an interesting and inspiring tale - a tale of the frustration and rebellion of a genius.

Beginnings

|

|

|

(This requires the Adobe Flash Player.)

In poems and exercises written during Milton's time at Cambridge, we see the seeds of poetic ambition germinating, and witness his growing interest in the English language and the service to which it could be put. In this time he wrote a number of notable short poems including 'L'Allegro' and 'Il Penseroso'. His poem 'On Shakespeare' was published in the second folio of Shakespeare's plays in 1632, the year he graduated from Cambridge with his MA.

Poetic Apprenticeship

Milton then spent a period of time at his father's home in Hammersmith (and later Horton) in private study - what has now been deemed his poetic apprenticeship. Works of this period include the masque now known as Comus, a courtly entertainment celebrating chastity in the face of temptation, written for an aristocratic family who had recently been involved in a licentious scandal. This period of time may seem uneventful, but it is interesting that while Milton felt he was destined for greatness, he had the maturity to see that he wasn't ready to compose a masterwork just yet, and indeed as well as the self-aggrandizing sections of his writing that are frequently noted, there is a concurrent, more subtle, theme of the piety of waiting for grace.

Towards the end of this period a young fellow at Christ's, Edward King, died in a shipwreck. In 1638 a book of poems composed by members of the college was published. Milton's pastoral elegy, Lycidas, was the most outstanding contribution, and is now regarded as one of the greatest lyric poems in the English language. The genre of elegy has many interesting tensions; its works are prompted by grief and are presented as an emotional outpouring, but often serve as self-conscious apprenticeship pieces for aspiring poets. Milton's complex poem mourns the loss of one so young, but also sees a galvanization of intent for the poet to rise to greatness, spurred on by fear at the example of King, a man cut down in his prime before glory had been achieved. In the middle section of the poem Milton takes the opportunity of contemplating King's piety to level some heavy criticism against the church in the first sally of his long attack against the prelates (or bishops).

In 1638, still unknown in England, Milton embarked on a fifteen-month Grand Tour (a visit to major places in Europe), as many young middle- and upper-class men did after university. He spent most of his time in Italy, and in spite of his anti-Catholic views, happily mingled with the literati and intelligentsia (including Galileo, then under house arrest for heresy, who is mentioned in Paradise Lost). Milton's poems in Latin and Italian won him great respect as a contemporary literary figure, but his return was a sharp comedown from this time of contentment. There was personal grief waiting for him - Charles Diodati had died, prompting the poem Epitaphium Damonis, a beautiful but heart-rending poem of genuine loss. He also returned to the turmoil of a country on the verge of civil war.

From a biographical point of view, Milton is an interesting subject as, unusually for the time, he wrote a fair amount about his poetic intentions in his poems, prose and notebooks. Around this time we know that he was contemplating subject matter for a great English work. He wrote about the idea of an epic on the legends of King Arthur, and listed nearly a hundred stories from biblical and British history as potential subjects for a drama. However, Milton was also the kind of person who could not just turn his back on civil injustice. He put his own creative ambitions on hold to focus on prose - as he called it, the work of his left hand - devoting himself to the betterment of his country by propagating his unorthodox belief in liberty.

Controversy - Divorce and Free Speech

He first became involved in religious dispute on the Presbyterian side by writing a series of anti-prelatical tracts in 1641-42. As well as being learned and intellectual, they are also filled with clever and amusing rhetoric, satire and invective. His views here are very Puritan and call for the suppression of the Catholic idolatry that he and others felt was increasingly present in the Church of England. At this stage Milton hadn't rejected monarchism, and he believed that the bishops were a threat to England and to the king.

In 1642 Milton married, perhaps unwisely, the seventeen-year-old Mary Powell, a girl from an unintellectual, royalist family. After a few weeks she went to visit her family and didn't return. It has been suggested that the outbreak of the first civil war, which initially went Charles I's way, may have made the Powells indisposed to favour their troublesome reformist son-in-law. These difficulties prompted Milton to write a petition in favour of divorce on the grounds of incompatibility (at the time divorce was only granted on grounds of adultery). Although Milton was motivated by a very high and pure ideal of marriage as an intellectual union, he was publicly attacked on all sides for libertinism. His later pamphlets defending the subject develop his notion of Christian liberty and the idea that the grace of God imbues the good Christian with the reasoning faculties to govern himself without recourse to worldly authority: this was considered a very dangerous and anarchical idea. The divorce saga ultimately resulted in probably the most famous of Milton's prose works. The government's attempt to suppress his ideas prompted the 1644 publication of Areopagitica, a treatise rejecting censorship before publication and arguing for freedom of inquiry (although Milton still reserved the right for governments to censor works after publication if they were immoral or went against Protestantism). Milton believed in the strength of truth and the importance of man being free to choose it.

I cannot praise a fugitive and cloistered virtue, unexercised and unbreathed, that never sallies out and sees her adversary, but slinks out of the race where that immortal garland is to be run for, not without dust and heat.

~Areopagitica (CPW, II.515)

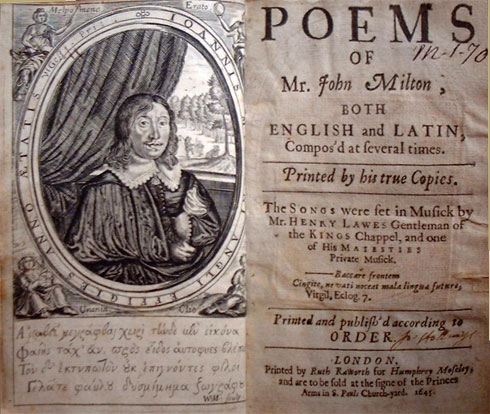

Later in the 1640s, Milton, who was working as a private tutor, became reconciled with his wife and she bore him a number of children. His home life at this time was not particularly content; a number of Mary's family moved in with the Miltons, creating a noisy atmosphere which was not particularly conducive to study or writing. As well as the pamphlets, Milton was also working on a history of Britain, and in 1646 he published a collection of his poetic works to date entitled Poems (this is dated 1645 in the old style).

|

BECOMING MITON: explore Milton's 1645 portrait |

Republicanism

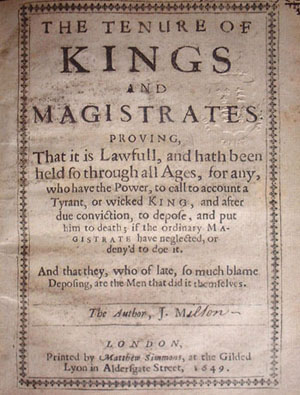

Two weeks after the execution of Charles I in 1649, Milton committed himself to the Republican side by publishing The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates in support of the regicide. His argument (which runs in direct opposition to Hobbes' Leviathan, to be published in 1651), was that a monarch's power is not absolute, but derived from the people he rules and held in accordance with a social contract. If a monarch breaks this contract by abusing his position, the people have the right to remove him from power. A few months later, Milton was appointed Secretary of Foreign Tongues to the Council of State; it was his job to translate documents and to write defences of the Commonwealth against Royalist attacks.

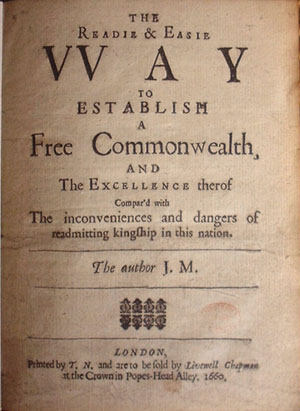

By the end of 1651, Milton's sight, which had been deteriorating since 1644, failed him completely. He was 43, blind, and with his great work still yet to be written. (Milton comments sadly on his blindness in the opening of Book III of Paradise Lost, and also in the powerful 'Sonnet 19'.) Despite these misfortunes he persevered with his secretarial duties until 1659, and published his last major pamphlet in 1660. It was a brave anti-monarchical protest in the face of the coming Restoration, which also expresses a feeling of despair at seeing his countrymen so eager to run back to servitude. There is a real sense of Milton as a lone but stalwart adherent to a greater truth rebelling against a false authority, much like the character Abdiel as portrayed in Book V of Paradise Lost.

When Charles II assumed control of the country in May 1660, Milton was in serious trouble. A number of Commonwealth leaders were imprisoned or executed, with some choosing to flee abroad for safety. Milton's friends hid him throughout the summer so he escaped immediate arrest, but his books were burnt and in parliament his name was proposed for exclusion from the Act of Pardon to be passed in August. Through the work of friends in high places, Milton wasn't excluded in the end, although he was arrested and held in custody for some months. It is popularly held that the invocation to Book VII of Paradise Lost, which talks of his 'mortal voice, unchanged' in spite of 'evil days' and 'dangers compassed round' (23-27), was written at, or perhaps in memory of, this time.

Later Years and Paradise Lost

|

William Faithorne's portrait of Milton aged 62, from a drawing made while he was writing Paradise Lost. |

Mary Powell died in 1652 and by 1656 Milton had married again, this time more happily. However his wife, Katherine Woodcock, died just two years later; she is the subject of the poignant 'Sonnet 23'. He married for the third time in 1663. Milton did not get on very well with his daughters, who were not academic and resented the schooling their father put them to. They stole from him and sold off portions of his library. Still, there is evidence that Milton was a reasonably sociable and agreeable man, amiably receiving visitors in spite of the pains of blindness and gout.

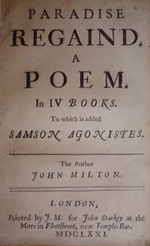

Milton began work on Paradise Lost at some point in the mid 1650s. It was composed orally by dictation to an amanuensis (or scribe) over the next decade, and was published in 1667. Despite Milton's unfortunate political reputation and the lack of serious interest in his previous poetic efforts, the epic was instantly recognized as a work of outstanding merit. These later years were spent in poetic endeavour. Paradise Lost was revised for the second edition in 1674, an enlarged edition of the Poems was published in 1673, and Paradise Regained and Samson Agonistes, probably written in the 1660s, were published in 1671 or 70.

|

Milton's cottage at Chalfont St Giles, where Paradise Lost was completed. |

Milton remained in London, with the exception of 1665-66 when he moved with his family to Chalfont St. Giles to escape the plague. This is the only one of Milton's houses which still stands, and it has been turned into a sort of shrine-cum-museum, open to the public. The house he grew up in on Bread Street was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666.

Milton died aged 65 on the 9th of November 1674, and was buried at St Giles, Cripplegate. He left behind some of the greatest works of the English language, and the memory of a man devoted to moral goodness and to liberty, with the strength to stand firm where others fell.

Further reading

Books

|

W.R. Parker, Milton: A Biography, 2 vols (Oxford, 1968). |

|

Barbara Lewalski, The Life of John Milton (Oxford, 2000). |

|

A.N. Wilson, A Life of John Milton (Oxford, 1983). |

|

Most editions of Milton's works will have biographical information in the introductory section at the front. Poetical Works, ed. Douglas Bush (Oxford, 1966), has a very readable biography, and Selected Prose, ed. C.A. Patrides (Harmondsworth, 1974), has a useful chronology of works and events during Milton's lifetime, and excerpts some of the biographical sections of Milton's own writing. |

On the web

|

Sophie Read (darkness visible contributor and a fellow of Christ's College) has written a biography that manages to be short and accessible but with an informative richness of detail: |

|

There is also a useful chronology of Milton's works on Christ's College's Milton 400 website: |

|

If you are interested in visiting Milton's cottage in Chalfont St. Giles, have a look at their website: |

OTHER CONTEXTS...

Religion: Milton and the Bible

| Copyright © 2008 Christ's College |

|