|

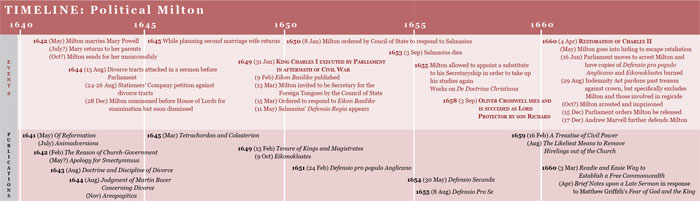

MILTON'S POLITICAL CONTEXT

The Political Climate of Milton's Day

The mid seventeenth-century was a time of great social and cultural turmoil. A series of political and military conflicts, now known as the English Civil War or the English Revolution, was waged intermittently between Parliamentarians and Royalists from 1642 to 1651. There were many factors contributing to the tensions between the Crown and Parliament, including Charles' marriage to the Catholic princess, Henrietta-Maria of France, and his desire to be involved in European wars. But the most interesting were the ideological questions being raised about the nature of government and authority. In the seventeenth century, the Crown played a much greater role in the running of the country than it does today. Parliament's power was growing, but before the Civil War, it was called and dissolved at the will of the monarch, and used mostly to issue taxes when the king needed money. Charles I believed in the 'divine right of kings' and ruled fairly autonomously, but much of Parliament believed that the king had a contractual obligation to the people to rule without tyranny. Parliamentarians were angry that Charles refused to call a Parliament for most of the 1630s, during which time he tried to levy what were considered to be illegal taxes. With Archbishop Laud, he tried to take the Church in the direction of High Anglicanism, which aroused suspicion that he was trying to revert the country to Catholicism. In 1649, after years of various political manoeuvres and bouts of fighting, King Charles I was executed for treason. For the next decade England had no monarch. Initially, a Commonwealth was formed and England was ruled by a republican government, but in 1653 Oliver Cromwell became Lord Protector, essentially a military dictator. He was succeeded by his son Richard in 1658, but because of faction fighting and Richard's lack of popularity as a leader, the republic failed. Charles II, the executed monarch's son, was declared King in the Restoration of 1660.

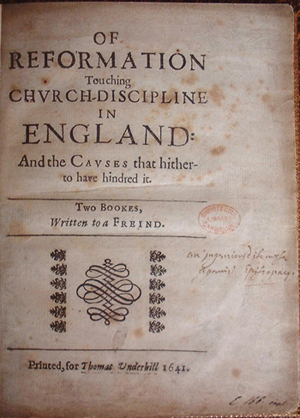

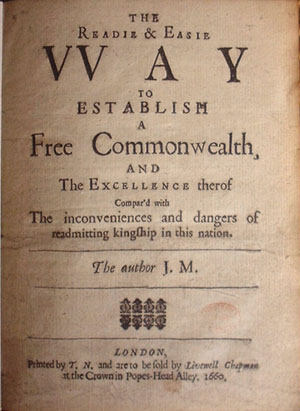

MiltonIn 1641 Milton published Of Reformation Touching Church-Discipline in England, marking the beginning of a career of political prose writing which would last almost until his death in 1674. Close analysis reveals a subtle change in his thought away from the youthful orthodoxy which had led him to consider ordination as a priest, and towards the increasingly heretical and subversive theology which typifies his later writings. However, the general thrust of his political writings is towards Puritan reformation in the church, and the replacement of the monarchy with a free commonwealth. His enduring support for Cromwell resulted in his appointment in 1649 as Secretary for Foreign Languages, a position which involved acting as the voice of the English revolution to the world at large. He remained stalwart in his belief in the republic, publishing The Readie and Easie Way to Establish a Free Commonwealth only a few months before Charles II's return in May 1660.

Milton's thought always appears highly integrated, and his political views cannot easily be separated either from his religious beliefs or from his poetry. An understanding of the politics of Paradise Lost must therefore be informed by an awareness of Milton's political life, his work as a prose writer, and the subversive elements of his theology.

On Kingship

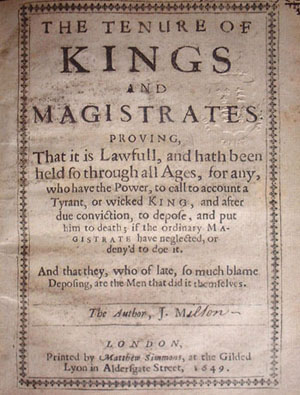

Milton's political views can be seen with particular clarity in relation to the execution of Charles I. Arguments both for and against Charles' reign exhibit a distinctively legal approach to scriptural exegesis (i.e. to the systematic interpretation and citation of passages from scripture). During his trial, Charles refused to make a plea to the court, claiming that no court could possess the necessary authority to try him. In thus denying the accountability of the monarch either to his subjects or to the law, Charles asserted that his rule was divinely ordained. The belief that the monarch is answerable only to God finds Biblical support in the Old Testament's records of God's endorsement of the kings of Israel and Judah, and in the New Testament in Romans 13:1-2. Writing in The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates (which was published only a month after Charles' execution in January 1649 and which serves primarily to justify the regicide), Milton adopts a markedly different interpretation of scripture: No man who knows aught can be so stupid to deny that all men naturally were born free, being the image and resemblance of God himself, and were, by privilege above all the creatures, born to command and not to obey. (CPW, III.198)The emphasis here is upon the nature of the created order, and upon man's position as part of the divine hierarchy. Milton argues that a tyrannical ruler contradicts this divine order, and that the role of the king is primarily to maintain this order, rather than to destabilize it. Arguing conceptually, historically and legally, Milton claims that the king must be understood as a servant of the people, bound to their service by the vows made in his coronation. He argues: It follows that to say kings are accountable to none but God, is the overturning of all law and government [...] for if the king fear not God, [...] we hold then our lives and estates by the tenure of his mere grace and mercy, as from a god, not a mortal magistrate. (CPW, III.204)

Poetry and PoliticsIt is important to recognise that just as Milton's political writings attain an extraordinary forcefulness through the use of literary devices, his poetry often overflows with political fervour and antagonism. Writing in Areopagitica, a tract denouncing restrictive censorship, Milton famously describes 'a noble and puissant nation rousing herself like a strong man after sleep, and shaking her invincible locks'; he goes on: 'methinks I see her as an eagle mewing her mighty youth, and kindling her undazzled eyes at the full midday beam' (CPW, II.558). The imagery is poetic, and the tone is elevated. The reverse effect can be found in many passages of Milton's poetry. In the penultimate speech of Samson Agonistes, Samson (before leaving to massacre the Philistines by pulling their temple down on their heads) argues: 'Masters' commands come with a power resistless | To such as owe them absolute subjection' (1404). In his consideration of divine authority, Samson seems to adopt the tone (and even the arguments) of Milton's early political writings. Both Samson contemplating mass murder and Milton attempting to justify regicide seem to fall into the same state of mind, and to share a common means of expression. Politics in Paradise LostIn attempting to situate Paradise Lost in its political context we face a particular critical choice, which rests upon the kind of context which we have in mind. On the one hand, we can examine the stylistic and argumentative similarities between sections of Paradise Lost and Milton's more explicitly political writings. On the other hand, Paradise Lost can be read as a political allegory, which is to say that events and characters in Paradise Lost can be aligned with aspects of the political context of the poem's creation. Satan's speeches provide the strongest example of a distinctively political voice appearing in the poem. When he addresses the fallen angels Milton draws on rhetorical techniques which are well-established in his political prose. Is this the region, this the soil, the clime, […]

|

| Copyright © 2008 Christ's College |

|