|

THE LEGACY OF PARADISE LOST

BY JON LAURENCE

When I first tried to read Paradise Lost, I remember being told (probably by Wikipedia) that it was an epic. I learnt that it was part of a great tradition including Homer, Virgil, Dante and Spenser, and that it frequently made references to these authors. Unfortunately, I didn't really know anything at all about epic writing, beyond what the notes at the back of the book could tell me. Even then, I didn't find it particularly helpful to know that the catalogue of fallen angels in Book I parodies lists of warriors in Homer. All the things I'd read that were closest to Milton had been written in response to his work, and what I found interesting was the way he'd inspired these later texts with which I was already familiar.

Milton and Pullman

|

|

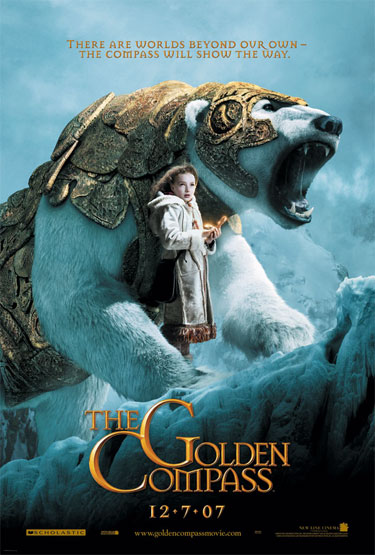

The Golden Compass (2007), film poster. A Hollywood film starring Nicole Kidman and Daniel Craig, based on the first novel of Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials trilogy.

|

The most obvious example of this was, of course, Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials trilogy (1995-2000). Pullman himself has said that his aim in writing His Dark Materials was to produce a version of Paradise Lost in three books for teenagers, and also that his method of characterization, in which individuals stand for abstract qualities, is modelled on Milton's work. Both works centre around an act of temptation - in Paradise Lost Satan is responsible for tempting Eve to sin, and at the end of Pullman's trilogy Mary Malone 'plays the serpent' and tempts Lyra.

Milton and Pullman share many of the same concerns: they are both preoccupied by authority and freedom, and how these ideals interact with God and religion. In both works, an original act of disobedience is responsible for bringing a new quality in the world - in Paradise Lost it is sin, and in His Dark Materials, Dust. It has been claimed that for Milton, the epitome of freedom involves (broadly speaking) abiding by Christian principles. However, for Pullman, God is a much more repressive, malign influence. Milton's God is a monarch, not a tyrant - he is a superior ruling over his inferiors, rather than someone unjustly raised above his peers (like Milton's Satan). Pullman's God is intentionally and irrefutably tyrannical. Of course, just how good Milton's God is has been widely debated by critics - whereas C. S. Lewis claims that Milton's work succeeds in its stated aim of justifying the ways of God to men, William Empson (Lewis' chief antagonist) has argued that Paradise Lost is good because it makes God look bad. Pullman's position in this debate is unequivocal; he says in his introduction, 'Blake said Milton was a true poet and of the Devil's party without knowing it. I am of the Devil's party and know it.'

Both Milton and Pullman also focus on knowledge and ignorance, and the ways in which these qualities are used to maintain authority. Pullman's God (and Magisterium) is much more explicitly concerned with maintaining its power by preventing people from gaining knowledge. In Paradise Lost, Satan advances this same argument in Book IX, suggesting that God might have forbidden man from eating of the Tree of Knowledge in order to keep him in a state of ignorance. Satan tries to cast God as intellectually repressive by saying to Eve:

Why then was this forbid? Why but to awe,

Why but to keep ye low and ignorant,

His worshippers... (IX.703)

Pullman takes up the (possibly specious) arguments that Satan advances in Paradise Lost, and develops them convincingly in his new setting.

Another common feature is a fascination with the possible existence of multiple worlds. In His Dark Materials, Will, Lyra and other characters are able to move between parallel worlds through windows cut by the 'subtle knife'. In Paradise Lost Satan makes his way:

Amongst innumerable stars, that shone

Stars distant, but nigh hand seemed other worlds,

Or other worlds they seemed, or happy isles,

Like those Hesperian gardens famed of old,

Fortunate fields, and groves and flowery vales,

Thrice happy isles, but who dwelt happy there

He stayed not to inquire... (III.565)

The idea of the possibility of multiple worlds is just a fleeting reference in Milton, but Pullman develops it and makes it central to his story.

Another interesting point of comparison is their portrayal of angels. Both controversially stress the physicality of angels by showing them eating - Raphael shares a meal with Adam in Book V, whilst Balthamos tries some Kendal Mint Cake offered by Will in The Amber Spyglass. Raphael's conversation implies that there is some material continuum between men and angels, but Pullman takes this to its extreme and the angel Baruch is revealed to have once been a man. Thanks to Raphael's description of angelic love (VIII.618-29), Milton's angels have been accused of homosexuality, a charge that C. S. Lewis and other Christian admirers of the work are keen to refute. In Milton the presentation is deliciously ambiguous, but Pullman's male angels, Baruch and Balthamos, are presented as deeply and even passionately (to use Pullman's word) in love with one another. As with the themes of ignorance and the depiction of other worlds, Pullman seizes on a glimpsed possibility in Milton's work and magnifies it, making it a definite reality and much more easily apparent to the reader.

Milton and the Romantics

Of course, Pullman was not the first writer to do this - countless other authors have been inspired to write their own versions of Milton's work, for a variety of different reasons. You probably won't be surprised to learn that Milton's Satan has been described as 'literature's first Romantic'. Now, even if you still haven't opened your copy of Paradise Lost and have skived all your English lessons, that description will probably sound oddly familiar... It is, unfortunately, from the back cover of the Penguin edition, so don't even think about using it in an exam (especially if you aren't quite sure what it means)!

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1818) is often viewed as one of the most powerful Romantic readings of Paradise Lost, sharing with Milton's work many of the same concerns about authority, and the relationship between creator and created (Victor Frankenstein and his monster vs. God and Adam). Both works show a preoccupation with the effects of solitude: Adam's desire for a companion (in answer to which God creates Eve) is analogous to the monster's yearnings for a bride, which Frankenstein refuses to satisfy.

Blake's long poem Milton (1805-08) is, unsurprisingly, heavily influenced by the poet's works, especially Paradise Lost. In another work, The Marriage of Heaven & Hell, Blake famously remarked that Milton was of the devil's party without knowing it. His main interest in Milton was in the presentation of Satan. Blake inspired a generation of scholars, including William Empson, and sowed the seed for the debate that would dominate Milton criticism for the twentieth century: did Milton really have sympathy for the devil?

Milton and Feminism

The feminist critics Gilbert and Gubar write about how Milton influenced women writers in the nineteenth century in their highly significant critical work The Madwoman in the Attic (1979). They claim that female writers felt Milton exemplified a patriarchal tradition because of the apparent misogyny found at various points in Paradise Lost, and they examine how writers such as Emily Brontë felt compelled to break from the male tradition Milton sets down.

Milton in Popular Culture today

Several modern novelists have also drawn a lot of inspiration from Milton's work. Pullman aside, the poet has also deeply inspired the American novelist Paul Auster, whose postmodern New York Trilogy (1985-86), picks up several Miltonic themes including the nature of Paradise and the relationship between words and things (both works are haunted by the idea of a perfect language). Also influenced by Milton is Jeffery Eugenides, whose novel Middlesex (2002) quotes from Paradise Lost at various points.

The 1997 film The Devil's Advocate also draws some loose inspiration from Milton's work, featuring a protagonist called John Milton (played by Al Pacino), various motifs involving heaven and hell, and Satan's famous line 'Better to reign in hell, than serve in heaven' (I.263).

You will also find lots of Paradise Lost in metal music. There is a British gothic metal group called Paradise Lost and the infamous Cradle of Filth have quoted the poem in their lyrics. 'Paradise Lost' has become a bit of a catchphrase in western culture, in music, film, TV and popular literature; but of course you already know that, because if you're reading this, you've probably googled 'Paradise Lost' already!

Inheritance: Milton's influences in writing Paradise Lost

|