|

MILTON'S RELIGIOUS CONTEXT

BY DAVID PARRY

|

|

|

In October 1656, the Quaker leader James Nayler rode into Bristol on a donkey, imitating Jesus Christ’s entry into Jerusalem. Women surrounded Nayler, laying palm leaves in front of him. This incident was debated in parliament for six weeks, many MPs arguing that Nayler should be put to death for blasphemy. In the end, a more lenient punishment was decided upon, and Nayler had his tongue drilled through.

Welcome to the seventeenth century!

In the past couple of years, religion has become headline news in a way that (at least in the UK) it hasn’t been for decades. This has taken politicians, journalists and academics by surprise, and many are struggling to catch up. In the academic world this has led to a new interest in writers like Milton.

In our time, we have a view of reality which separates out the public space of ‘facts’ (where we put science and politics) and the private space of ‘values’ (where we put morality and religion). This distinction was less sharp 400 years ago. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century writers frequently used ‘religious’ arguments and quotations from the Bible to defend ideas about politics, literature and even fishing.

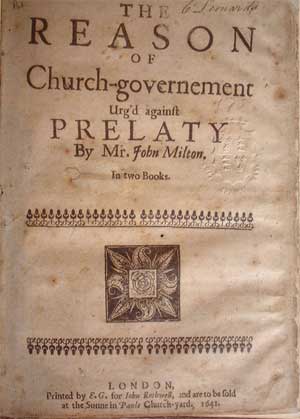

Milton cannot be understood out of his religious context. When he was a young man, Milton was preparing to become a clergyman in the Church of England, as his parents had intended. However, he later decided that because ‘tyranny had invaded the Church’ he could not be ordained in the Church of England with a good conscience (The Reason of Church-Government, CPW I.823). Why was this? Well, to explain this, we need to go back to the sixteenth century, the century before Milton.

The Reformation

In the later Middle Ages, many people in Europe were concerned about problems in the church including corruption, low educational standards for priests, and religious apathy among the general population. In the early sixteenth century, some people, such as Martin Luther in Germany and John Calvin in France and Switzerland, started to argue that the root problem in the church was that its message had drifted from the original message of Jesus Christ and his first followers. Around this time the Bible was printed and translated into national languages (not just Latin) and so became available to a wider audience than ever before.

The reformers argued that the Bible teaches that we enter into a relationship with God which brings us eternal life and the forgiveness of sins simply by putting our trust in Jesus Christ and his sacrifice of himself for our sins. They held that this message had become confused by the Church’s emphasis on religious observance, good works, and the financial support of the Church as means of attaining salvation, ideas which suggested that people could buy their way into God’s good books. Some reformers stayed loyal to the Catholic Church, and instigated changes collectively known as the Counter-Reformation, but many reformers left or were expelled from the Church and began founding their own churches. Those who belonged to these reform movements outside the Catholic Church became known as Protestants.

The Reformation was a messy business, which was tangled up with all kinds of economic, political and personal motives. Non-theological reasons for becoming Protestant might include cashing in on the market for selling books on these controversial ideas, or, for kings and princes, increasing your political power by ditching the authority of the Pope. In England, Henry VIII broke away from the authority of the Pope and made himself ‘the only supreme head on earth of the Church of England’ (Act of Supremacy, 1534). This was largely motivated by political reasons related to his divorce of Catherine of Aragon and subsequent marriage to Anne Boleyn. Henry VIII wasn’t too interested in the new religious ideas floating around, and, in fact, was strongly opposed to some of them, but his break with the Pope opened a door through which Protestant theology started to come.

Henry’s son Edward VI and his advisers promoted a much more thorough form of Protestantism when he came to the throne in 1547. However, when Edward died in 1553, the pendulum swung right back the other way. When Edward’s sister Mary came to the throne, she gave England back to the Pope, and started burning Protestants. Unsurprisingly, many Protestants ran away to places under Protestant control in Europe, such as parts of Switzerland and Germany. When Mary died in 1558, and her Protestant sister Elizabeth became queen, these people came home. You would have thought they would be happy...

Puritanism

Well, some of them were. But after a while things started to bother some of the returning Protestant leaders. Elizabeth made England Protestant (again), but for some, it wasn’t Protestant enough. Elizabeth wanted to hold the country together and so tried to manage the national church in a way that included as many people as possible. Because of this, the Church of England signed up to a Protestant theology, but many of the outward features of the old church stayed the same – such as bishops, ministers wearing robes, and using a written service book. For some people these things could be used perfectly well in a Protestant context, but others thought that because they couldn’t find these things in the Bible, they shouldn’t be used. These people are often known as Puritans. Church historian Patrick Collinson has called the Puritans ‘hot Protestants’, meaning people who were keen to reform the Church of England further to be more extremely Protestant.

Different scholars have suggested different ways of defining Puritanism. Some of the common characteristics include emphasis on the importance of preaching and on the importance of spiritual experience. Milton is often counted as a Puritan, though this depends on which definition of Puritanism you are thinking of.

When Milton studied at Cambridge, his college, Christ’s, was a stronghold of Puritanism. Some of the fellows (i.e. tutors and lecturers) of the college got in trouble with the university authorities for attacking some of the practices of worship used in the college chapel and for speaking to each other in English instead of Latin. As the seventeenth century went on, Puritans became concerned with the way the Church of England, particularly under Archbishop William Laud, was starting to move back to ritual and ceremonial practices found in the Catholic Church, and was starting to downplay the importance of preaching from the Bible.

The Puritans often suffered (and still suffer) from a negative stereotype of being miserable killjoys. While there are some things about some Puritans which might fit this view, such as the Puritan attack on theatre, many of them lived out their faith in a joyful way and some of them really enjoyed the natural world and the arts. (Milton fits in here, since he wrote some of his poems to be set to music and helped to put on shows for the nobility.) All of them believed that ordinary people were important and wanted the whole population to be educated to understand God’s message to them.

At the time of the English Civil War (a series of disputes and battles between 1642-51), Puritanism was generally associated with the Parliamentarian side, and Laudianism with King Charles’ supporters. These religious disagreements contributed to the mix of tensions leading to the wars. When Parliament won the war and set up a republic, the ideas of different Puritan groups had an input into political decision-making.

One possible explanation for why the republican government didn’t ultimately succeed is that when the Puritans got into power, they split into their different factions. There was a whole spectrum of different religious groups in the broader Puritan movement, some more bizarre than others, but the distinction which is most significant for thinking about Milton is the distinction between Presbyterians and Independents. The Presbyterians wanted to keep a national church, but to have it led by a council of ministers (presbyters) who had equal status to each other, instead of by bishops. The Independents wanted each specific congregation to be able to decide for itself its beliefs and practices. Milton seems to have moved from working with the Presbyterians against the bishops, to being disillusioned with the Presbyterian desire to bring in a new system of religious control. His sympathies probably moved to the Independent side.

Milton’s own beliefs

It’s hard to pin down Milton’s exact beliefs, except to say that he was a strong Protestant who emphasised the freedom of the individual. It is fair to say that Milton probably held a number of controversial beliefs, such as the idea that the soul dies with the body and will be resurrected with the body on the Day of Judgement. He certainly held controversial views on divorce and may well have had sympathies with Arminianism, a new variant of Protestant theology, which, in contrast with mainstream Calvinism, emphasised human freedom rather than God’s ruling power over all things.

Milton probably held heretical views, which contradict orthodox Christian belief, on the Trinity. Instead of the standard Christian belief that God is one God in three persons – Father, Son and Holy Spirit – Milton seems to have believed that these were three separate beings, and that the Son and Spirit were not equal with the Father. These ideas are found in a theological work traditionally attributed to Milton, De Doctrina Christiana (meaning ‘On Christian Teaching’), although there is currently some debate over whether Milton wrote it.

These debates about Milton’s theological beliefs influence how we read Paradise Lost, where, for example, it seems to me that the Son is a being who is greater than the angels but not strictly equal to God the Father.

Paradise Lost was written after the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, who returned the Church of England to how it was in his father’s time before the Civil War. It seemed as if the Puritan cause had been defeated. We might see Abdiel in Books V and VI of Paradise Lost as representing this Puritan cause, standing for purity and truth in the midst of a corrupt society. In Book V, lines 809-48, Abdiel defends a radical obedience to God with ‘zeal’, even though his manner seems ‘out of season’ and ‘singular and rash’ (V.849-51). Many Puritans seemed this way to the people around them. It seems that Milton became increasingly isolated, politically and religiously, in his later life. Perhaps he saw himself as an Abdiel figure: ‘Among the faithless, faithful only he’ (Paradise Lost, V.897).

Suggested further reading

![]() Christopher Hill, The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution (Penguin, 1972).

Christopher Hill, The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution (Penguin, 1972).

This book is about the wilder religious groups in the mid-seventeenth century. If you want to read more about people like James Nayler, this is quite fun.

![]() N. H. Keeble, ‘Milton and Puritanism’, in Thomas N. Corns (ed.), A Companion to Milton (Blackwell, 2001), pp. 124-140.

N. H. Keeble, ‘Milton and Puritanism’, in Thomas N. Corns (ed.), A Companion to Milton (Blackwell, 2001), pp. 124-140.

Keeble does a great job of summarising quickly and accessibly, but without oversimplifying, how Milton relates to various aspects and strands of Puritanism.

![]() Jameela Lares, Milton and the Preaching Arts (Duquesne University Press/James Clarke, 2001).

Jameela Lares, Milton and the Preaching Arts (Duquesne University Press/James Clarke, 2001).

This book argues that although Milton decided not to be ordained in the Church of England, he never gave up his sense of calling to a preaching ministry, and preached through his writing instead.

OTHER CONTEXTS...

Religion: Milton and the Bible

| Copyright © 2008 Christ's College |

|