|

MILTON AND PERFORMANCE

BY KATHARINE FLETCHER |

|

|

Milton and Drama?

Milton was intimately familiar with classical drama, and the poems 'On Shakespeare' and 'L'Allegro' show his admiration for contemporary drama. However, he was no playwright. In his early twenties, he wrote two entertainments: 'Arcades' and the masque now known as Comus. While they were written for performance, they are not dramatic in the way we'd think of, for example, a Shakespeare play being. Entertainments were performed in aristocratic homes or at the royal court, usually by members of a noble family, for a private audience. They involved great spectacle - lavish costumes and scenery, music and dancing - but the exercise was a symbolic expression of social order, often presenting moral values, not a dramatic exploration of story or character. Comus has a more developed story than many masques (which, like Milton's epic, centres around temptation), but is also highly philosophical and discursive in its presentation. In the years after Paradise Lost was published, Milton also wrote a tragedy in the Greek style, Samson Agonistes, but in his introduction he made it clear that it was never intended for the stage.

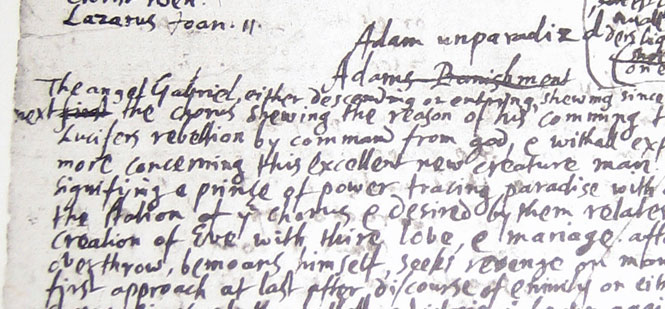

By 1642, Milton had written a detailed outline for a play, a tragedy, called Adam Unparadised. The outline has much in common with Paradise Lost and is considered a stage in the development of Milton's thinking on the great epic. However, when Milton came to compose Paradise Lost in the late 1650s, he had abandoned the idea of presenting the story as a play. There are a number of reasons why this might have been. In the Renaissance there were strict rules about the presentation of religious subjects in the theatre: you could not speak God's name or represent him in person on the stage, neither could you act out Biblical scenes. Also, in 1642, after much Puritan protest against their licentiousness, the theatres were closed, and not re-opened until the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660. If we compare the outline of the play to the epic, we see that in Adam Unparadised the focus was much more on the human story and less on the celestial or demonic. It is possible that having decided against writing a play Milton then expanded his subject, but he could also have abandoned the dramatic mode on realizing that he couldn't fit these larger sequences into a play.

Paradise Lost in performance: History

Paradise Lost was adapted for stage in Milton's own lifetime, with the blind poet's consent. In 1674, the Poet Laureate, John Dryden, a great admirer of the work (despite his opposing political and religious views), turned the epic into a libretto for an opera to be called The State of Innocence. However, the music was never written and the libretto has never been performed.

There hadn't been many other attempts to adapt Paradise Lost for performance until recent years. The late 1970s saw some interesting interpretations, with Penderecki's opera Paradise Lost (libretto by Christopher Fry), and Peter Minshall's Paradise Lost-themed band for Trinidad Carnival.

The last few years have been particularly fruitful. In 2002, David G. Burns started reciting certain books at various fringe theatres, and 2004 saw two theatre productions: the Bristol version (by David Farr) and the Northampton version (adapted by Ben Power and directed by Rupert Goold).

Paradise Lost in Performance: Practice

And so to the big question: how would you adapt Milton's epic?

First, you need to choose your medium. Stage and screen are probably the most amenable (and what I will concentrate on here), but stop and think for a moment: what would be the implications of performing Paradise Lost in a wordless medium? Minshall's band unfolded a narrative as it paraded through Trinidad Carnival; how would you do this using just costume and music? Could you tell the story through dance or mime? Would it be wrong to abandon Milton's words, and how would you indicate that your version was based on Paradise Lost and not just Christian lore? How would you tackle moments where the action of speaking is important, for example, when the serpent persuades Eve of the forbidden fruit's power to elevate those who consume it by the fact that he can speak like a man?

Then, the big question is what do you leave out? Readings of the whole poem take around twelve hours: you probably have three. David Burns believes in fidelity to Milton's text and his recitations do not abridge; however, he performs just one or two books at a time. The stage adaptations both contained the full narrative arc and so condensed the text heavily. There is no right or wrong way to do this, but some decisions will work better than others. A good model for thinking about this is Peter Jackson's film trilogy, The Lord of the Rings. While Jackson was obviously unable to reproduce Tolkien's books in their entirety, he remained true to their spirit by identifying and stripping down to the narrative and emotional core of the story, then building up from there with carefully selected details which, amongst other things, gesture back towards the larger mythos of the books.

How will you deal with dialogue? Character's speeches are often very long and dense. This is fine in a book, where you can pause to take it all in, but in a live performance, words exist in time. You need to make sure that your audience will still be able to follow what's going on. You don't want to dumb the text down, but at the same time you don't want your audience to lose sight of the core idea while they try to negotiate complex syntax or follow lines and lines of classical references. Live performance also has a different dynamic, and a series of lengthy monologues can make a play or film feel very static.

Another big question is, do you want to have a narrator? There will be key parts of the narrative you probably won't want to lose, for example the famous opening. In a film, voiceover could be used effectively, particularly for economically establishing new scenes. In a play, however, an off-stage narrator might seem strange. There are plays (for example, the musical Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat or stage versions of Dylan Thomas' Under Milk Wood) which have onstage narrators, although you may feel this creates an intermediary layer that distances the audience from the story. You would then also have to decide how to present the narrator. Should he (or she) be dressed as Milton? As a denizen of Heaven? Of Hell? Ben Power's adaptation had a very effective solution, extending the Son's remit to fulfill this role. Being a player in the events that unfolded, he didn't distance the audience from the plot. In fact, the increased presence of the Son, and his ability to address the audience directly, helped emphasize their involvement with him and the story (viewed within the Christian framework that the work assumes).

Presenting Milton's images visually also bears a host of problems. It has been suggested that the reason Dryden's The State of Innocence was never performed was because the scope was too great. How on earth would you stage the war in Heaven? In Books V and VI, Raphael has a difficult enough time describing his narrative for human senses without having to show it as well. On film, this could be done with modern special effects, but in a theatre it is more difficult. But there are some things which even special effects can't really demonstrate. How would you show 'darkness visible'? This type of resistant imagery is problematic on screen, but can be handled well on stage, as the theatre is a much more receptive ground for suspension of belief and acceptance of metaphorical presentation. The Bristol production was very stark in terms of design, and Hell was created by lighting effects, the wretchedness of its inhabitants, and descriptions both by the Son as narrator and subsumed into the devils' speeches. The rebels' long fall from heaven was very simply implied by the slow flailing movements of their outstretched limbs as they lay with their bodies supported across chairs, like some sort of bizarre cabaret.

Thinking of Paradise Lost as a production also highlights some of the problems the reader faces of bringing in baggage from our fallen world into the scenes of Heaven or Eden. Adam and Eve the characters should of course be naked before the Fall, but confronting an audience with naked actors (as both the Northampton and Bristol productions did) highlights our own fallen attitude to nudity. For a film-maker, large amounts of nudity present practical problems of certification, and there will be instances where it would be inappropriate on stage, for example in a school production.

Final Thoughts

One of the biggest difficulties of performance is that it forces you to make interpretive decisions. A line of text can remain ambiguous on the printed page, as Milton's often does, but when spoken out loud only one pattern of stress can be applied at any one time, just as imagery that resists a constant form has to be pushed one way or another if it is to be presented physically. You may not come up with definitive solutions to these sorts of questions, but they will certainly highlight areas of representational tension within Milton's poem.

LEARN ABOUT MILTON AND THE ARTS...

| Copyright © 2008 Christ's College |

|